A Soldier’s Life in World War I: Irving Greenwald

Based on the life of Irving Greenwald

Reading a soldier’s diary requires a tremendous amount of patience. For the soldiers of the First World War, the actual fighting took up a minimal amount of their time. In reality, the life of a soldier in war is filled with a tremendous amount of minutia. Reading a soldier’s diary requires time to digest all of that soldier’s life while in service, from his day-to-day life in training, through what it means to endure life in the trenches and to muster heroic courage in combat.

For the Library of Congress’s commemoration of the centennial of the First World War, I was invited to write a new play based on the life of Irving Greenwald, a soldier from WWI. Greenwald was part of the Lost Battalion, and the Library’s Veterans History Project preserves his diary. I will perform a one-man play on Veteran’s Day.

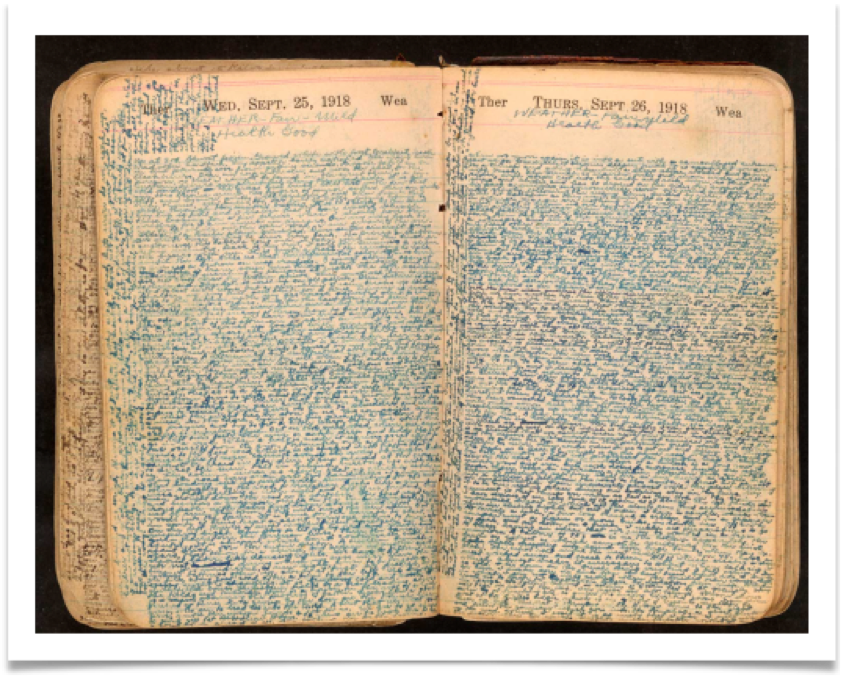

Irving Greenwald left 465 days of his diary entries, and I set out in May to read all of them, to read ten days’ worth of his diary entries each day. I aimed to complete the entire diary in a little over a month. Some days I read more, and some days I read less.

Luckily, since Greenwald’s diary had been digitized, the process was simple—much easier than my last project, The American Soldier. That play is based on letters written by veterans from the American Revolution all the way through current day Afghanistan, taking eight years to research and write. I researched individual letters, mostly at the New York Public Library, and photocopied passages from those letters I found especially compelling. I sorted them into folders of letters about the Vietnam War, WWII, the Iraq War, the Revolutionary War, etc. I typed them up by hand—tedious and time-consuming—before finally fleshing them out into monologues that I could work on as an actor.

But because Greenwald’s diary was digitized, I could turn the whole thing into a PDF, upload it to my Kindle. I could then highlight passages I found compelling and pull out only what struck me into one document, and that would become the foundation of the play, An American Soldier’s Journey Home. To find the best parts of the diary, I had to read it—every single page of it.

Greenwald, fortunately, was a very eloquent writer, so there was plenty to pull from, even in moments that weren’t thrilling. I sorted the passages under basic headings like Camp, Food, Funny, Death, Trench, and more. I used a color-coding system: red meant this was important, and green was a cue to stop and re-read the material.

“I have just witnessed the wonder of life and the helplessness of death. Why do men do it? Why do they kill? Why do they destroy? The cost of it all, the futility of it. The war will never be won on the field of battle. Why not end it all and spare men and women.”

By early summer, I had the diary sorted into five basic sections: his camp life, being shipped off to France, arriving in Europe, his trench life, and his time in the hospital after being wounded. It took another month to tease out all the best passages of a particular topic. The play could not be longer than 45 to 55 minutes, so my challenge was to trim down the word count to trim down the run time. I knew that my last play The American Soldier was only 7,500 words, and it ran 57 minutes. I had only about two more months to finish my play and was at nearly 30,000 words—more than 20,000 words too many. The hardest thing to do in writing, especially when it is poetic and eloquent writing that you have fallen in love with, is deleting. I stayed up late many nights reading and re-reading, trying to get a feel for how I wanted to tell Greenwald’s story. By August, I had the draft down to 17,000 words. I kept repeating to myself, Get to the point, Douglas, get to the point!

I took about a week off to digest the material, and then I began editing again. By the end of August, I had the draft down to 15,000 words. From there, I moved passages around and added just a bit of connective tissue to help Irving’s writing take the shape of a fluid monologue. It was time to read it out loud, which is a critical step for getting a sense of whether a play is working. So I started reading this early draft out loud to my wife and a few others, and something still felt off.

It is a frightening feeling as a writer when you feel stuck and can’t move the story forward. I have lived through this feeling before, so I know it doesn’t last forever, but when you are in it, it feels as if you will never see the light at the end of the tunnel. I tried listening to music, something I lean on for inspiration. I looked at images of World War I—the people, the places. And at the beginning of September, an epiphany arrived: I knew how to tell my story. As if the writing gods said, OK, Douglas, you have suffered enough, and you may now move forward. Within one day, I was down to 5,800 words.

With this draft and being a month out from the show, I felt good about taking the play into my memory, crafting my character so that I could share the story of Irving Greenwald’s life in service just in time for November 11th, 2017.

Color Coding System

Red meant the material was important, and Green meant to me to stop and re-read the material.